Have you been tempted to sell all your stocks this year? If yes, you are not alone. Many people, especially those near or in retirement, have done just that – sold all their stocks and stock funds. I was shocked by this statistic in a recent Wall Street Journal article: At Fidelity Investments, nearly 33% of investors age 65 and older sold ALL their stock holdings between February and May 2020, versus just 18% across all age groups. No doubt many of these sales happened as stocks were losing up to a third of their value, before bottoming in late March and rising steadily so far to near record highs.

I read the rest of the Wall Street Journal article with some sadness because it profiled well-off people in their 60s who had sold all their equity holdings. Someone had sold all stocks and went to cash 12 years ago, but could never find the right time to get back in the market. A business owner had sold all stock while counting on the sale of his company to fund retirement. But that business is now worth much less due to the pandemic.

We know the urge to sell can be overwhelming if you do not have a plan in place for where your cash will come from during retirement or your portfolio is too stock-heavy. In these situations and others, you do not have what we call an anchor during the inevitable terrible storm. Drifting at sea, you’re bound to seek the safest harbor, which is all cash. And that is exactly what many have done.

To avoid panic selling, we focus intently on liquidity (current and future cash needs), risk tolerance and risk management. Typically, I suggest that my clients who are near, or in, retirement hold enough cash or liquid assets to cover two years’ worth of spending. Whether that is inside a portfolio as short-term bonds or held separately, this is a security blanket that you can wrap around yourself when you feel the urge to sell all.

Ask Before You Sell

When clients call me asking to sell some or most of the stocks in their portfolio, I sometimes ask them these three questions, and we talk through them:

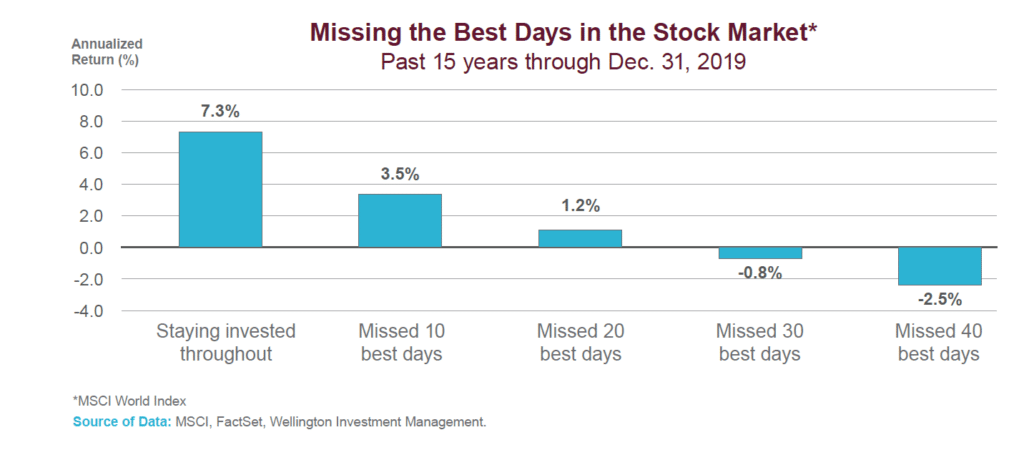

***Do you really want to be a market timer? Selling all your stock holdings and going into cash is actually a type of market timing. While this may seem safe, it can actually be more risky than doing nothing (assuming you have planned ahead for the inevitable market downturn by setting aside some cash). That’s because when you sell, you must then decide when to get back into the market. And you can be sidelined for months or even years as you wait for a good time to reinvest. Studies routinely show that missing the stock market’s best days can be very hurtful to your long-term return.

***How will your returns keep up with inflation? Even when inflation is low, as it is now, cash is losing value every day because it is not earning anything or next to nothing, yet housing, food, education, and healthcare costs keep rising. Perhaps you have large real estate holdings and feel you don’t need equities. But real estate has its own drawbacks. For one, you may not be able to sell it as easily as you think.

With money market funds typically paying way less than 1% now, and trillions in stimulus funds propping up asset prices, there is reason to think inflation could eventually make a comeback. You want to have at least some allocation to stocks, even if you are deep into retirement, since stocks can be a hedge against inflation.

***Has your risk tolerance really changed or are you just panicked? When we construct investment portfolios for clients, we explore fully what would be a comfortable long-term allocation to stocks. The answer varies greatly depending on their assets, finances, life goals. By getting to know each of our clients and their families, we can advise on levels of stock ownership that should allow for good long-term growth without causing panic during downturns. That’s because that allocation reflects their tolerance for risk, in context of cash balances and other investments. We assume that the stock market will have periods of scary losses and also years of relatively low returns. But this is better than not being in the market at all for long periods of time.